Reminiscences of WW2 from My Grandparents – Part 2

ANZAC Day. A day that Australians and New Zealanders remember of those who went to war. A day to remember those who never made it home. And it is also a day to remember those who were left at home during the war and afterwards.

Last week I wrote “Reminiscences of WW2 from My Grandparents – Part 1” which is primarily an interview with my grandparents Evelyn and Cecil Hannaford about their experiences during World War 2.

This interview, which was done as a high school project a number of years ago by a friend who interviewed them, is written as a transcript. So this is my grandparents talking about their own experiences during the war, In. THEIR. OWN. WORDS! Not as history books records it, but as they experienced it.

As it was a long interview I decided to split it into two, and this is the continuation.

Continuation of the interview …

What type of weather was it?

Mr H. It was winter time. Then when we got up to Trincomalee [Sri Lanka] it was summer time, in the tropics. We were out in the bay and the sister ship, Mary, went out into the harbour and they had all the port holes open, light shining everywhere. We had to have ours shut and it was hot.

Did you have enough food?

Mrs H. Well, everyone was rationed.

What were the ration books like?

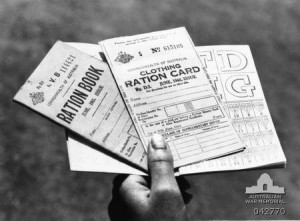

Mrs H. We were given ration books and you had to have so many coupons for tea and sugar and butter. We weren’t troubled about the butter because we made our own.

Mrs H. We had to go to the shop or on the other hand thee was one of the grocers that used to come around and take the order and then deliver it the next week. You always had to have your order for the next week ready. Another thing that was scarce was steel. When that went out we had no steel wool for the pots and pans. That all had to go into the bullets and so forth. There were quite a few things like that … silvo, brasso.

Mr H. Because the troops had to polish their buttons. No. They did it in the early days, but during the war they didn’t. Couldn’t have anything shiny.

Mrs H. Anyway, the ration books were a pesky nuisance. I think we had to have them for clothing eventually. It started off just with the eats and then it got down to the clothings, sheets, things like that.

Mr H. Petrol. You were only allowed a certain number of gallons. About so much a week or a month.

Mrs H. Your coupons would accumulate with petrol. Because if you didn’t use it one week you could get the two lots the next. But it was always safer to get it each week, otherwise somebody else might have got in before you and got the extra.

Who told you where you had to work?

Mr H. There was a man power committee or something, under the government.

Mr H. You had to register.

Mr H. They directed labour to certain industries.

Mrs H. You put down what you wanted to do or where you prefer to go, and what your present occupation was, whether you were on a farm, or what you were doing. Anyhow, they said I couldn’t go to the engineering department and so I had to stay on the farm and help with the vegetables. Because all the men were taken.

Mrs H. When one brother went into the army, it just left the other brother at home. So when it was to feeding cows and that sort of thing, that was how I learnt to drive the car. But it was the tractor I learnt on and then I rose to the car!

So you really learnt independence then?

Mrs H. Yes.

What was it like just having one man around?

Mrs H. It was pretty awful at times. It anything happened to him, I would have to the do the milk round, like if he got sick or anything, because had a milk round as well.

Did you have to take and precautions in case of an attack?

Mrs H. Yes. We had to black out every night. That was putting black coverings over your windows, so you couldn’t see any lights. We had to black out anywhere where there was a likelihood of light getting through. Churches had to have the same thing. Well, all public places had to do it as well as the homes.

Mr H. All the cars had to have the top half of their lights painted black, dimmed. So it only showed a little bit of light down on the road. Pretty hectic driving in those days.

Mrs H. I don’t think your car was used much through the war years. I think we walked everywhere.

Mr H. We had to save petrol, didn’t we.

Mrs H. Yes. But it was illegal to have any lights shining.

What would they do it they saw them?

Mr H. Probably be fired.

Mrs H. Be told off or whatever.

Did you ever feel that Australia would be invaded?

Mrs H. When it got to Darwin we certainly did. It got a bit close to home.

How did you feel when you heard about the bombing of Darwin?

Mrs H. It made your heart sink a bit. It was Australia. Your country.

Were you married before you (Mr H.) went?

Mrs H. Yes. It was two or three months after we married that you (Mr H.) went.

Was that hard, him going?

Mrs H. It made you wonder what had happened.

How did you feel when you heard about the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and then on Nagasaki in 1945?

Mrs H. Oh! Terrific. I threw my hands and through “that will be the end of it”.

How did you feel when the war ended?

Mrs H. V for Victory. We had to put up two fingers, V. V for Victory!

Did you celebrate in any way?

Mr H. We were together at the Park when peace was declared.

So you (Mr H.) were back in Australia?

Mr H. Yes. Actually I was released before the end of the war. Because it must have been when the bomb hit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they could see the end in sight and so quite a few of us were released. I didn’t go to the islands at all. As far as I got was Queensland, after I came back from the Middle East. Then stayed at Cairns, Atherton for quite a while.

Mrs H. He had a brother, younger that was in the gunners (artillery) and they were bringing him back to the Islands.

Mr H. He was at Rabaul, New Britain. He was there all the time. The Japs got him there.

Mrs H. They’ve never heard of him since.

What was it like coming home from the war?

Mr H. Quite a thrill. Glad to be back and forget all about it.

Mrs H. We met in Rundle Street. It was by accident.

Mr H. That was when we came back from the Middle East. I got out on leave and was going to go home with a carrier who used to come up to Cudlee Creek, used to run through Lobethal. Anyway, I didn’t have any pyjamas and I had to go and get a pair. So I went up to Gibsons and bought a pair of PJs. Mum (Mrs H.) was in a little restaurant just below Gibsons and as I walked past she must have spotted me.

So what did you do?

Mr H. She came home with me then!

So it was quite a shock. Were you going to surprise her?

Mrs H. They never let you know their movements.

Mr H. I never expected to see anyone in town. I intended to get home anyway.

What did you do after the war?

Mr H. Lived at Cudlee Creek, where we live now.

Mrs H. When Hiroshima was bombed, these guys didn’t have to go back in to the army and so that was the end of it. So then you (Mr H.) applied to get out and he was given it.

Do you have any other experiences?

Mr H. I remember one night we were camped along the beach at El Alamein. During the day we used to go up onto a hill and overlook the enemy. I used to drive this armoured car up and park it in a little dugout and then they would go up in this little cave and watch. All I had to do was wait at the car. Anyhow, at night, we used to go down to the beach and camp on the sandhills. We would make our bed alongside a “slit trench’. Which was a narrow trench, just big enough to slide into. We would make our bed by there in case of any enemy attack. This particular night there was an attack and what we did was we just rolled into the trenches.

Mr H. There were a few shots fired. Another chap had his tyre punctured up on his car, but the armoured car I had didn’t have any damage done to it. None of us were injured at all, so that was alright.

Mr H. One thing about being in the artillery was that we were quite a long way back from the fighting.

Did you hear the guns?

Mr H. Oh yes, you could hear them.

How did you feel?

Mr H. It was a thrill on the opening night at El Alamein, because there were big guns behind us and then our lot and then the smaller guns further on. The noise was terrific. you got used to it after a while.

Mrs H. One of the lads that came home said that he was in the aircraft, anyway he reckoned that whenever the guns were firing you felt as big as a house because bullets were falling all around you and you thought “it will be me next”.

Were you glad that you weren’t fighting?

Mr H. Yes. Yes. I never intended to take on the infantry, because that was just not my piece of cake. Some of the chaps they seem to like it.

Mrs H. Some were more daring that others.

What did you think of Hitler?

Mr H. He was a nasty man. Mussolini wasn’t much better.

Mrs H. They were two of a kind.

Mr H. Much alike.

After Dunkirk, when Churchill was saying “Don’t give up, keep on going”.

Mrs H. He was the one that kept the army together.

Mr H. Churchill had such a wonderful personality. A good leader.

Mrs H. He was a good soldier himself. He knew how to get the best out of people.

Mr H. If he wasn’t there it might have been quite a different story.

——————

Between my earlier post and this one they cover the greater portion of the interview, but not the entire thing.

Before finishing I really must thank Cathryn Trollope, again for not only allowing me to use her interview in my blog, but also for asking if my grandparents would be interested in doing the interview in the first place. Myself, together with other family members wholeheartedly THANKYOU!!

Thank you for sharing the interviews. They have been most interesting..