They Died in the Asylum

Parkside Lunatic Asylum is the original name for the building that was subsequently renamed to Parkside Mental Hospital, then Glenside Hospital and more recently Glenside Health Services.

Situated on Fullarton Road at Glenside, it is in one of Adelaide’s leafy eastern suburbs and is by outwards appearance, a magnificent place. But the asylum was far from that for the inmates at the asylum, and sadly for so many it was their last home.

The Parkside Lunatic Asylum was opened in 1870 initially housing men, but by the 1880s men, women and children were being housed there. It housed not only those suffering from mental illness, but also people with intellectual disabilities and medical conditions like epilepsy.

While browsing around on Trove, I found this article in the Adelaide Advertiser, 14 January 1910, and was saddened by the fact that there was so many who even in a six month period, died without family nearby.

– Wilhelm Heinrich Dittich (71), July 5, pulmonary disease and cardiac failure

– Judy (aboriginal female), (60), July 10, gastritis and cardiac failure

– Guiseppe Castagneth (58), August 8, apoplexy and cerebral disease

– Rosalie Russell (63), August 20, hepatic disease and ascites

– Theodosia Byrne (78), August 20, apoplexy and senile decay

– Sarah Jane Hayes (35), August 29, phthisis and exhaustion

– Bridget (alias Annie) Evans, (42), August 29, suicide by hanging

– William Conway (36) September 1, general paralysis and apoplexy

– Dora Knout (80), September 2 cardiac disease and senile decay

– William Carruthers (75), September 5, diarrhoea and senile decay

– Thomas Paddock (70) September 17, cardiac disease and senile decay

– Alfred Perfect (48) September 18, apoplexy and paralysis

– George Henry Holmes (52), September 26, pulmonary tuberculosis and exhaustion

– Isaac Mowatt (69), November 2, empyæmia

– Mary McNulty (60), November 13, Pulmonary tuberculosis and exhaustion

– Oscar Genske (55), December 6, cardiac disease and paralysis

– John Kew Dawson (69), December 10, senile decay and exhaustion.

Glenside Hospital, formerly the Parkside Lunatic Asylum, taken 2015

Source: denisbin Flickr

– Parkside Lunatic Asylum on Find & Connect

– Untold Stories of the Parkside Lunatic Asylum on Weekend Notes

Trove Tuesday: “There’s Gold in Them Hills …”

The tiny town of Gumeracha in the Adelaide Hills is well known these days for being the home of the world’s biggest rocking horse, the annual medieval fair, and of course wines. But believe it not, at one stage, Gumeracha was well known for its goldfields.

Many who have connections to the area would have heard of Watts Gully Road at Forreston (previously North Gumeracha), this was one area where gold was, and was first found by James Watts back in 1884. Dead Horse Gully is near Watts Gully Road, and this was another of Gumeracha’s gold diggings areas.

For my Trove Tuesday post, I’ve found the following article which discusses the Dead Horse Gully goldfields … and for someone who didn’t know about them (yes me), I found it fasinating, so thought I’d share it with you. Note: old references to this place list is as Deadhorse Gully (two words), or even Dead-Horse Gully (with a hyphen), current day spelling is Dead Horse Gully (three words). For consistency, I’m using the three word version.

From the South Australian Register, dated Saturday 14 March 1885 …

THE GOLD FIND AT GUMERACHA.

During the last few days large number of men have arrived at Dead-Horse Gully on the gold rush. Now nearly 100 men are working in the gully around Mount Crawford. The rush was so great that on Thurs-day Hill & Co. put on a special coach from Adelaide. The rush is at Mount Crawford, about seven miles north-east of Gumeracha. To get at the field it is necessary to turn off the main road at North Gumeracha-road and to go right through that township. For the first three miles there is a good district road, but after that there is merely a vehicle track through the scrub and rough hilly ground. Deadhorse Gully is about a mile and a half long, and is thickly wooded with colonial honeysuckle. On entering the gully several holes where trials have been made are noticeable. These are in some cases three or four feet deep; in other cases even more. Right along the gully a large number of claims, about fifty, are being worked. These are of various depths. One or two men have gone to a depth of 18 feet before bottoming. The soil is gravelly and patched with black sand in nearly all the claims. In this soil gold is found in a great many cases.The gully runs due east and west, and the whole length has been pegged out. In some cases the men say that they have got payable gold, while others have got simply the colour. One man, who has been working in the gully for three years with his mate, kept the matter quiet, but every fortnight he used to take £8 or £9 worth of gold into Gumeracha. He has been very successful, and has a nugget in his possession weighing 3 oz. Other men have done very well. One showed several nice nuggets weighing under an ounce. He had got all the gold from coarse rough surface. The average depth of the claims before striking the drift is about ten feet. Of course, gold is got at a less depth than that in some places. One man only went four feet before he came on stuff which, when panned, yielded several specks. Some men who have been up several days have been unsuccessful and have cleared out, but their places were quickly filled. Several men are on the road tramping it to the gully. It is considered that there is gold in the drift from the reef on the hill on the north side of the gully. Experienced miners on the ground agree that all the gullies in the vicinity contain gold, and that several abound with gold to quite as great an extent as this. Two or three men have marked out claims in other gullies.

Cabs, carts, drays, wagons, and vehicles of all descriptions are on the ground. There are a number of tents for the men to sleep in, but others are content to lie under trees or to sleep in carts. There are men of all occupations amongst those present — old miners, clerks, cabmen, labourers, several boys, and sailors.

At the East-End Gully there is an indication of a good reef. Some quartz picked, up on the surface showed copper, gold, and pyrites. The great difficulty to contend with in working claims is water. When the men get down ten feet or so water from the hills soaks through this, and has caused the abandonment of one or two claims. Provisions for the camp are brought round by the storekeepers of Gumeracha, but a store in a galvanized-iron structure of about twelve feet by nine is to be opened on Saturday.

On Thursday the Warden of the Goldfields visited the ground, and considers that there is good gold in the gully, but not enough of the mineral for the hundred men who are now on the spot. The whole bottom of the valley has been pegged out. Mr. Hack says that the gullies on either side of this one have gold, and advises the men to spread out. If they do this there is very little doubt but that the industry will get a good start, as the surface is good – so good that he believes that the reefs, of which there are several in the hills around and about, must be very rich.

The samples of ore found are of what is known as burnt ore. It would be very foolish for any more men to go on at present to the gully, as all the likely ground is holed, but the other gullies, to which provisions could be taken daily, offer a good field for prospecting.

Owing to the crude character of the utensils some gold has probably been lost. If the reef is fallen in with at these claims the men will be unable to crush the stone, but none appear anxious to do other than sink surface claims. During the day a large number of visitors go over the ground. The best find so far was a nugget weighing 3 oz.

Fascinating isn’t it, though I still find it hard to envisage just what it was like back then. You can find the whole original article on Trove here.

So there’s just one more little piece of a small town’s amazing history for you.

For those who are not familiar with the term Trove Tuesday, it is a popular theme within the Australian genealogy blogging community, as we browse the Trove website (Australia’s old newspapers that are online AND FREE), find an article that interests us, and write about it … usually on a Tuesday. You can find all of my past Trove Tuesday posts here.

Emigration from England to South Australia in the 1800s

The “Mayflower” is ‘the ship’ in US history. The first ship to transport passengers from England to the United States in 1620. 102 people, all hoping to start a new life on the other side of the Atlantic.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

From then on, there was a big push to get skilled labourers from England to emigrate to the new colony, and as an enticement they were offered free passage (assisted passage). Of course there was still the option for anyone who wished to emigrate to pay their own way (known as unassisted passage), but many took up the offer of the emigration scheme, and as a result these pioneers helped make South Australia what it is today.

But as with anything that’s free, there were some rules and regulations.

I came across this list of rules for those wanting assisted passage in the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, dated 27 February 1839, and it’s truly fascinating.

RULES FOR EMIGRATION

- The Act of Parliament declares that the whole of the funds arising from the sale of lands, and the rent of pasture, shall form an Emigration Fund, to be employed in affording a free passage to the Colony from Great Britain and Ireland for poorer persons; “provided that they shall, as far as possible, be adult persons of both sexes in equal proportions, and not exceeding the age of 30 years.”

- With a view to carrying this provision into effect, the Commissioners offer a free passage to the Colony (including provisions and medical attendance during the voyage) to persons of the following description.

- Agricultural laborers, Shepherds, Bakers, Blacksmiths, Braziers, and Tinmen, Smiths, Shipwrights, Boat-builders, Butchers, Wheelwrights, Sawyers, Cabinetmakers, Coopers, Curriers, Farriers, Millwrights, Harness-makers, Lime-burners, and all persons engaged in the erection of buildings.

- Persons engaged in the above occupations, who may apply for a free passage to South Australia, must be able to give satisfactory references to show that they are honest, sober, industrious, and of general good character.

- They must be real laborers, going out to work for wages in the colony, of sound mind and body, not less than 15, nor more than 30 years of age, and married. The Marriage Certificate must be produced. The rule as to age is occasionally departed from in favour of the parents of large families.

- To the wives of such laborers as are then sent out, the Commissioners offer a free passage with their husbands.

- To single women a free passage will be granted, provided they go out under the protection of their parents, or near relatives, or under actual engagement as servants to ladies going as cabin passengers on board the same vessel. The preference will be give to those accustomed to farm and dairy work, to seamstresses, strawplatters, and domestic servants.

- The children of parents sent out by the Commissioners will receive a free passage, if they are under one, or fall 15 years of age at the time of embarkation. For all other children £5 each must be paid before embarkation by their parents or friends, or by the Parish. It will be useless to apply for a relaxation of this rule.

- Persons who are ineligible to be conveyed out by the Emigration Fund, if not disqualified on account of character, will be allowed to accompany the free Emigrants on paying to the commissioners the bare contract price of passage, which is usually between £15 and £17 for each adult person. The charges for children are as follows: under one year of age, no charge; one year of age but under seven, one-third of the charge for adults; seven years of age and under fourteen, one-half the charge for adults. A passage intermediate between a cabin and steerage passage may also be obtained of the Commissioners at a cost exceeding that of the steerage passage by one-half. Each intermediate passenger is entitled to half a cabin with some slight comforts in addition to those enjoyed by the steerage passengers.

- All Emigrants, adults as well as children, must have been vaccinated.

- Emigrants will, for the most part, embark at the Port of London, but if any considerable number should offer themselves in the neighbourhood of any port of Great Britain or Ireland, arrangement will, if possible, be made for their embarkation at such port.

- The expense of reaching the port of embarkation must be borne by the emigrants, but on the day appointed for their embarkation, they will be received, even though the departure of the ship should be delayed, and will be put to no further expense.

- Every adult Emigrant is allowed to take half-a-ton weight or twenty measured cubic feet of baggage. Extra baggage is liable to charge at the rate of £2.10s the ton.

- The Emigrants must provide the bedding for themselves and children, and the necessary tools of their own trades; the other articles most useful for emigrants to take with them, are strong plain clothing, or the materials for making clothes upon the passage. In providing clothing, it should be remembered that the usual length of the voyage is about four months.

- On the arrival of the Emigrants in the colony, they will be received by an Officer, who will supply their immediate wants, assist them in reaching the place of their destination, be ready to advise with them in case of difficulty, and at all times give them employment at reduced wages on the Government works, if from any cause they should be unable to obtain it elsewhere. The Emigrants will, however, be at perfect liberty to engage themselves to any one willing to employ them, and will make their own bargain for wages. This arrangement, while it leaves the Emigrant free to act as he may think right, manifestly renders it impossible for the Commissioners to give any exact information as to the amount of wages to be obtained; they can merely state that hitherto wages have been very much higher than in England.

So a free passage together with the social and economic conditions in England at the time, enticed our ancestors to pack up their whole life, spend four months on board a ship, travelling to an unknown country on the other side of the world, to start start again. We can’t imagine it can we.

The pioneers. They were brave beyond our understanding.

“Dear Friends” … Letter From an Emigrant in 1864

So what was life like for those who emigrated to South Australia back in the 1800s? Generally you’re only likely to find this information from letters written to family or friends in the ‘old country’, or otherwise from diaries. So it was a surprise to find an article on Trove about an emigrant who not only came to South Australia, but actually settled in the tiny town of Gumeraka (note the alternate spelling of Gumeracha).

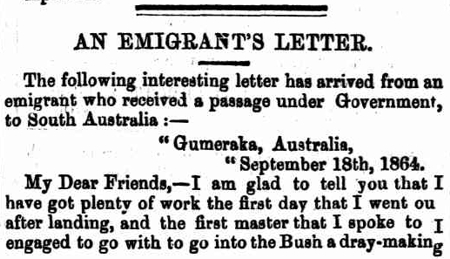

Written in 1864 to some friends in England (or maybe Wales), it was produced as an article the Scotts Circular (Newport, Wales), and then in The Adelaide Express, 22 April 1865 (as reproduced below). The writer details what it was like for him and his family with housing food, work and wages, neighbours and other businesses all getting a mention. What we don’t know is who the author of the letter is. Still, it makes for an interesting read.

In 1864 the town of Gumeracha was not very old, having only been laid out in the 1850s (for more on that click here).

The article starts off with “The following interesting letter has arrived from an emigrant who received a passage under Government, to South Australia.”——————————

An Emigrant’s Letter, Adelaide Express, 22 April 1865 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article207600900

The text below is a full transcript of the article. Note the paragraphs have been added in by me to make it easier to read.

AN EMIGRANT’S LETTER.

Gumeraka, Australia,

September 18th, 1864.

My Dear Friends, I am glad to tell you that I have got plenty of work the first day that I went on after landing, and the first master that I spoke to I engaged to go with to go into the Bush a dray-making and waggon-making at the wheelwrighting trade, at the rate of wages I will give you, and you can see whether it is as good as in England. I think there is a better chance for a working man to get on here; the wages that I am going to have is, with lodgings, that is a hut and firewood as much as I like to burn, and all my food, and I have meat every meal, and eggs and tea every meal, and pudding every day, and £1 10s. per week, if that is not; good send and let me know of it; that was the first chance that I had.

I think it as good as £2 10s per week, and my wife have a good many things gave her, and the children get plenty to eat at the farm which we live close to.

Our hut have got canvas windows instead of glass, but they do out here as there is not many people to see out here, only at the farm house. They keep a blacksmith’s shop and a wheelwright’s shop, but it is about a mile from the farm, and they send our meals down to us; there is another wheelwright that married the daughter which live at the farm; their house is like a cow-shed-in England, but they got plenty of money, they are Scotch people; and they are good people to work with, and my wife and children are quite well and myself in good health.

We can live as cheap as we could in England, and butter is 8d. per pound; beef, 2 1/2d. to 3d.; mutton, 2d. to 4d. per pound; sugar, 4d.; tea, 2s. 6d. to 3s.; bread now is rather dear Is. a gallon (?) ; beer, 10d. per quart and 1s.

There is plenty of work out here if people will but come out to try. If any body will come out I will go and meet them, and keep them till they can get work, or I will ‘try and see if I could get them a place, but there is nobody out of work here; cloth is about the same as in England.

Please to read this to all of the shop, and tell them that I am very much obliged to them for what they done for me when I were at home, but if I can do anything for any of them in any way, I will do it with the greatest pleasure of doing it to any of my old shopmates; please to tell them all to write to me, and I will write to them in return, and please to send me some newspapers, and I will send they some.—Scotts Circular, (Newport, Wales.)

So there you have it. That’s what life was like in Gumeracha back in 1864, and no doubt similar in other country towns, taken from a firsthand account.

![earliest known photo of Gumeracha, taken c1870 [click for a larger image]](http://www.lonetester.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Earliest-photo-of-Gumeracha-1870s-300x179.jpg)