The First Traffic Lights in Australia

When were the first traffic lights installed in Australia? It’s an interesting question, and one that once asked, makes you intrigued to find out … well it did me anyway.

So that’s what today’s history lesson is all about. When were the first traffic lights installed in each of the Australian states?

Of course I headed to the one and only magnificent Trove to find out, and you might just be as surprised as I was!

SYDNEY – 13 October 1933

Friday, 13 October 1933 was when Sydney’s (and Australia’s) first traffic lights began operating. The lights were installed at the intersection of Market and Kent Streets in city of Sydney, and were switched on at 11am, by the then Minister for Transport, Colonel Michael Bruxner. You can see a fabulous photo of the traffic lights here.

BRISBANE – 21 January 1936

At 3pm on Tuesday, 21 January 1936 a large crowd gathered in the CBD to watch the switching on of the first traffic lights in Brisbane. These were installed at the intersection of Ann, Upper Albert and Roma Streets.

HOBART – 27 January 1937

This one surprised me as I never realised that Hobart had traffic lights so early. But the newspapers reported the grand occasion which you can read on the link below. Just before 11am on Wednesday the 27th of January 1937 the lights were turned on at the intersection of Elizabeth and Liverpool streets.

ADELAIDE – 13 April 1937

Tuesday, 13 April 1937 was Adelaide’s big day, as that’s when Adelaide’s first traffic lights were turned on. These were installed at various intersections along King William Street in the city.

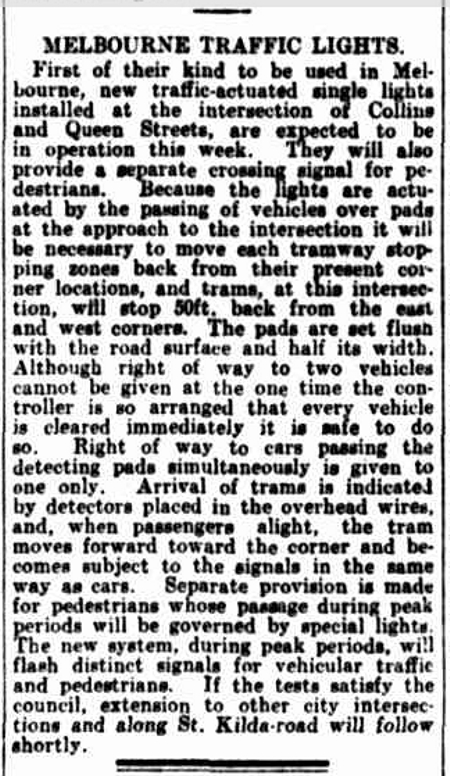

MELBOURNE – late December 1937

The Melbourne public had to adapt to traffic lights around Christmas time in 1937. The “new traffic-actuated single lights” were installed at the intersection of Collins and Queen Streets in Melbourne’s CDB, and “they will also provide a separate crossing signal for pedestrians”. As these were deemed a success others at St Kilda Road followed shortly afterwards.

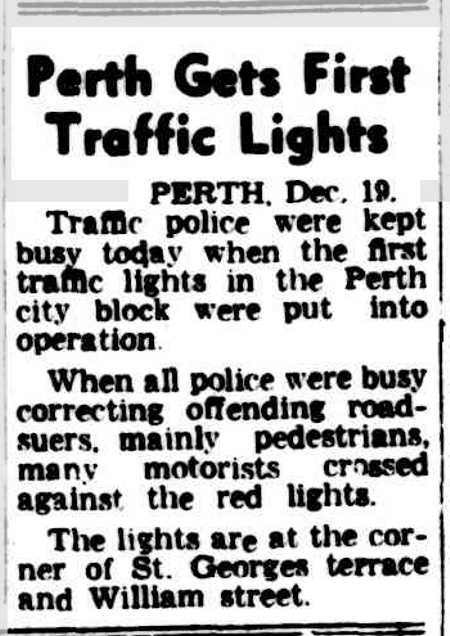

PERTH – 19 December 1954

December was the time for yet another set of traffic lights to be turned on. This time it was Perth. Their first set of traffic lights was installed at the St Georges Terrace and William Street intersection.

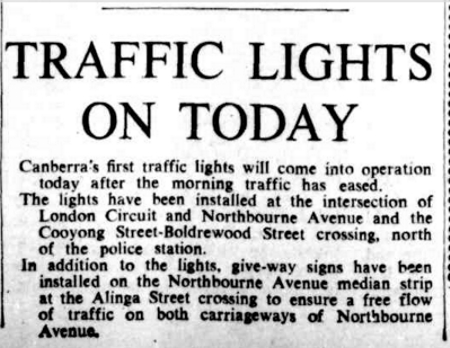

CANBERRA – 23 October 1965

Canberra’s first two sets of traffic lights were brought into operation on Saturday, the 23rd of October 1965. The traffic lights were installed at the intersection of Northbourne Avenue and London Circuit, and Northbourne Avenue and Cooyong Street.

DARWIN – approx 1960s-1970s

I was unable to find an official date, but I did find a reference in someone’s memories of life in Darwin which says “there were no traffic lights anywhere at the time. The first set of traffic lights I remember were at the intersection of Bagot Road with the Stuart Highway!” You can read the full article here. If anyone can provide a date please let me know, and I’ll be happy to update my post.

A Thankyou to the Captain

As an avid Trovite, I love reading the old newspapers (as so many of us do). And yet, I am still amazed at the very cool stuff you can find in the old newspapers.

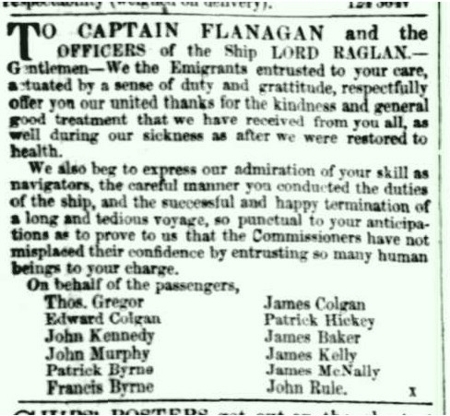

Take for instance one of my recent finds. A friend asked me to see what I could find on the “Lord Raglan” 1854 voyage to South Australia.

So after some general Googling to find out the basic details (the ship left Plymouth, Devon 16 July 1854, and arrived in Port Adelaide, South Australia on 23 October 1854), I found a copy of the original passenger list on the State Library of South Australia website. I also found references to it on the Passengers in History site, and The Ships List.

Anyway so then I headed off to Trove , and I came up with a thankyou message that the passengers had written to the Captain of the Lord Raglan ship, and they put it publicly in the the newspaper. How cool is that?

It’s great to know that Captain Flanagan and his crew looked after their passengers on the long voyage to a new life.

Another newspaper entry I found relating to the Lord Raglan, quotes the following …

The fine new ship Lord Raglan, 923 tons register, Captain Flanagan, for Adelaide, and the Appoline, of 500 tons, for Melbourne, having embarked their respective complements of emigrants from the Government dept, at Plymouth, sailed on Sunday. The Lord Raglan belongs to Messrs. W. Nicholson and Sons, of Sunderland, and has been fitted up on a most excellent plan, the result of the experience of Captain Lean, R.N., the Government emigration officer in London. Among other advantages, one-third of each bed can be turned up from the sides of the ship, so as to admit of a free passage two feet wide, all round her, and thus secure an effectual means of cleansing and ventilating the vessel every day. Her emigrants, numbering 369 souls, were under the charge of Surgeon Superintendent W. Brett.

This was from the South Australian Register, 21 October 1854, pg. 2.

Note: Trovite = a person who loves hanging out on the Trove website.

Britain’s Playing Card Tax

Anyone who is vaguely familiar with British social history will be aware that they have had some “different” (by that, yes I mean rather odd) taxes over the years.

Take for instance the Hearth Tax in which you paid based on the number of fireplaces in your house, the Window Tax was the same but was based on the number of windows you had. The Clock Tax, the Candle Tax, the Soap Tax, even a Beard Tax are others just to mention a few – and all were used as a means to raise funds for the government of the day.

But here we’re talking about a tax on Playing Cards.

Yes, truly. The humble deck of cards was taxed (not forgetting dice as well).

In reality they had been taxed since the late 1500s, but in 1710 the English Government dramatically raised the taxes on them, which the manufacturer was then liable for. As the rate of tax was equivalent to 12 times the price of a cheap pack of cards, you can imagine that there were forgeries.

But in a bid to prevent this, each manufacturer had their own ‘mark’, and would hand stamp their mark on the Ace of Spades to show that it was a legit version.

Still, as the taxes were excessive, forgeries happened.

And while creating forgeries of playing cards doesn’t sound too drastic, if you were caught making them the result was hanging.

While the tax itself is surprising enough, what’s even more surprising is that tax continued through until 1960. That’s 250 years! Incredible.

So if you are lucky enough to have an old deck of cards, take a closer look at it. Check out the maker, and in particular have a close look at the Ace of Spades and see if it has the hand stamp on it.

The “Fitzjames”, South Australia’s Floating Prison

A largely unknown piece of South Australia’s history is the fact that there was a prison ship (or hulk) anchored just off of Port Adelaide at Largs Bay. While we’ve heard of them in the UK, who knew that Australia had them too?

In 1876, the ‘Fitzjames’ a ship of 1,200 tons, was purchased by the South Australian Government from Mr Donaldson in Melbourne, and cost them £2,800. It was bought with the intention to use it as a quarantine ship. There’s more about this in the Evening Journal, 15 April 1876 …

“She will be moored near the North Arm, and will be used for patients while the cottage on Torrens Island will be fitted up and set apart for the convalescents. In view of the large influx of population to the colony it is important to have ample quarantine accommodation and the arrangements are now in progress will secure this without the delay which would be caused by waiting for the erection of suitable buildings.”

However by 1880 and through until 1891, the ‘Fitzjames’ served as a “Reformatory” for over 100 young boys aged from 8 through to 16.

From the Evening Journal dated 11 June 1879 …

“… if the hulk Fitzjames were not required for quarantine purposes after the buildings on Torrens Island were completed the Government would consider the advisability of converting her into a training-ship for Reformatory boys”

The first boys to call the Fitzjames home, were ones transferred from the Boys’ Reformatory at Magill in March 1880. Some had committed serious crimes, while others were guilty of petty theft, or simply deemed uncontrollable.

The inspection reports which you’ll find in the newspapers, generally give a fairly favourable report, as well as giving an idea of what the boys’ day was like. So while it’s been called a ‘prison ship’ or ‘prison hulk’, the descriptions doesn’t exactly make it sound prison-like, so I’m thinking ‘reformatory hulk’ would be a more accurate term.

Anyway here’s a snippet from the The Express and Telepgraph newspaper, dated 4 February 1887 written by the Inspector-General of Schools, Mr L.W. Stanton when he visited. Click on the link above for the full report.

“I visited the hulk Fitzjames on the 21st instant, and remained from 10.30 till 2.50. My visit was quite unexpected, and I found a majority of the boys at school and under perfect control. Those absent were engaged at work in the tailor’s and shoemaker’s shops for the morning; they attended school in the afternoon. I was informed they were all over 13 years of age, and that they received instructions from the teacher on three afternoons per week. Those under 13 attended full time. There were present in the morning 35, and in the afternoon 61, The furniture and apparatus were scrupulously clean. There was a satisfactory supply of reading books, copy books, exercise books, slates, and minor requirements, I noticed no maps, there being no place to hang any. … I found that the tuition was carried out on the lines of the standard for our public and provisional schools, and that the master had an ‘intelligent grasp of the work there laid down. … I was on the whole favorably impressed with Mr. Schrader’s work, and that I am satisfied of his fitness for his post, his industry, and his conscientious discharge of his duty. He appeared to me to control the boys with a proper degree of mildness combined with firmness, and they on their side seemed respectful, orderly, intelligent, and happy.”

However not all was great, as this report in Evening Journal from 15 November 1884 tells us …

The Commission took evidence with regard to the safety of the hulk Fitzjames, now lying at Largs Bay in deep water with sixty-four boys on board. The report read as follows:—” I have surveyed this vessel. I find the caulking below the copper very bad, in several places the oakum is completely decayed, being so bad that a rule can be pushed through from the back of the seams to the copper, and difficult to keep the ship afloat. I examined a leak on the starboard side in the lower hold, which was caused by a butt being open between two timbers. This has been temporarily stopped by wedging from inside. Through wedging one of the planks has been started from the timber nearly an inch, there by endangering the safety of the ship, as in heavy weather she must make a quantity of water. The top sides are much decayed, and planking under the copper must be bad, as in several places the nails have no hold on the planks to retain the sheets of copper from dropping off.

And the conditions continue to deteriorate, as the report from 30 June 1888 suggests …

The condition of the hulk was now worse than it was previous to the temporary repairs she underwent some time ago, and at the time he was writing there was over 3 feet of water in the hold, although the lads have been pumping morning and evening for over four hours each time, and this, considering their age and stamina, was far too great a strain on their constitutions, so he respectfully solicited the board’s interest and advice as to the immediate renovation of the vessel.

…as the timber for the vessel was cut 50 years ago she must be in a state of deterioration … She ought to be condemned …

By August 1891 they had given up on the vessel, and she was offered at a public auction with no reserve, and the Fitzjames hulk was sold for £130.

From emigrant ship, to cargo ship, to quarantine hulk, and then prison (or reformatory) hulk … she had seen it all.