Anzac Day: A Message from the Battlefield

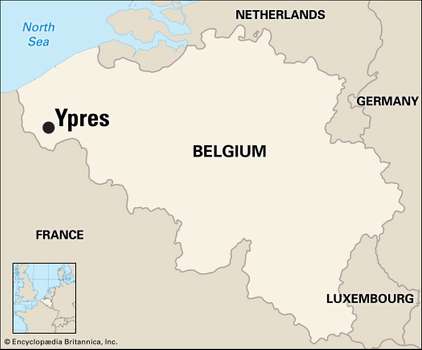

For Anzac Day this year I’m focussing on Ypres, a city in Belgium that’s on the French border. A prosperous place that in 1914 had a population of around 18,000 people.

Just for reference, Ypres is the Belgian version of the name, while the Australian Diggers knew it as as “Wipers”. And nowadays it is often known by it’s Dutch version, “Ieper”, which is pronounced as “ee-per”.

From November 1914 through until November 1917 Ypres was devastated by war and as you would expect, deserted by its inhabitants. Over that 4 year period, there were over 38,000 Australians who were killed or wounded in the Ypres battles, while the total number of casualties for all sides climbed into the many hundreds of thousands.

Captain Frank Hurley was an Australian official military photographer who was in Ypres during 1918 and captured many unforgettable images of the destruction and the lives of the Australian soldiers during the Third Battle of Ypres (also known as the Battle of Passchendaele). The photograph at the top of this post is one of his very well-known ones. The State Library of New South Wales has a large collection of his war photographs (and diaries) online, so if you’re interested feel free to click here to view them.

Anyway this year I’m remembering my great grandpa, Otto Rafael Winter. I have written about him before, including his service with the Australian military, but this time I’m highlighting a family heirloom.

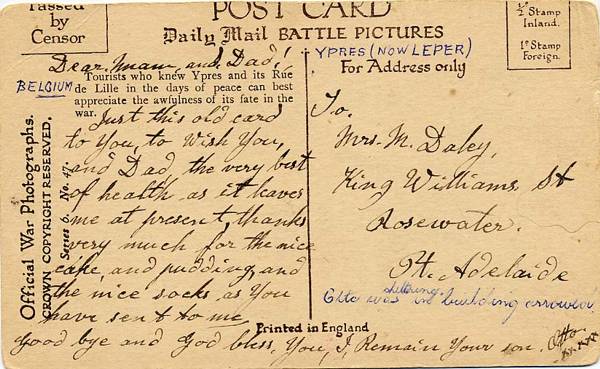

The postcard pictured below is one of the very few heirlooms that exist from my Winter family, and it’s a postcard that Otto sent from Ypres, Belgium (one of the places he was deployed to) to his parents-in-law, John and Margaret Daley, in South Australia.

The postcard itself is a photograph of what the city of Ypres looked like after two years of war: bombed out buildings and crumbling ruins. But on it he’s drawn little arrows, with a notation on the back written by his daughter saying “Otto was sheltering in building arrowed”. He’s also written a date of 1916 on it, but I’m unsure of when the postcard was actually sent.

A transcript of the what he wrote is as follows:

Dear Mam, and Dad!

Just this old card to you, to wish you and Dad the very best of health as it leaves me at present, thanks very much for the nice cake, and pudding, and the nice socks as you have sent to me.

Good bye and God bless you,

I remain you son, Otto xxxxx

—————————–

To me it’s not ‘just’ a postcard. It’s a tiny picture into what his life was like during the war, and what he saw. It also a little memento that shows me how much he cared for his parents-in-law. Firstly taking the time to write to them. Thanking them for the parcels of cake, pudding and socks that they’d sent. Calling them mam and dad. And signing off as “I remain your son”. That shows he cared, right?

Otto was a merchant seaman from Finland who jumped ship in Australia, and made it his home, so much so, that in 1909 he chose to become an Australian citizen and was naturalised.

He met a local girl, Irene Daley. Married her in June 1915 and their first child was born a few months later.

With the war dragging on much longer than it was expected, the call for more volunteers came and Otto signed up in January 1916, and by May 1916 he was in Belgium. A tunneller, he was in Ypres in March 1918 when he was poisoned in a mustard gas attack and was sent to an Australian military hospital in France to recover.

Otto was lucky. Not only did he survive the mustard gas, but also the rest of the war despite other injuries. In June 1919 he made it home to his wife and family, and lived on until he was 81.

Lest We Forget!

Remembering Tarakan, 1 June 1945

Anzac Day, a day of remembrance of those who fought and died for our country. Whether they lived or died, nothing was ever the same again for those who went, as well as those at home.

For today’s Anzac Day post, I looked at those from my own family who were involved in war – there have been many over the years in the various wars, but this times I’ve chosen to write about Harold Roy Winter, my grandma’s brother who was involved in World War 2.

I’ll start off by saying that the military knows him as “Roy Harold Winter”, rather than “Harold Roy Winter”, simply (or so the story goes) as there was another person already signed up with that name so he switched it, so for this purpose I’ll go with the military version.

Born in Victoria, he grew up in Adelaide, and signed up as a young 25 year old ready to fight for his country. He was assigned to the 2/48th Battalion Australian Infantry Battalion, and got to see to world … and war!

Reading through the letters he wrote to family while he was in the army, he describes going overseas as a great adventure, as well as describing the monotony of army life. He also writes about the strength of the hospital staff …

“The efficiency, determination and sacrifices to their job are a magnificent credit to them, and only we who have experienced it can give a true value to their worth. In many cases, patients were being attended by orderlies who were just as ill, or in some cases even worse. Such is to the spirit of the A.I.F. and it will keep all of us going till we die or win through.”

But it was a sketch that he drew of a battle scene that I wanted to highlight today.

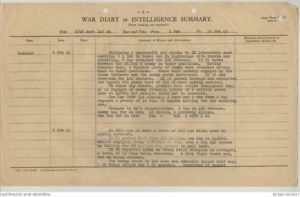

Captioned: Attack on Hill 102, Tarakan, June 1st 1945, I wanted to know more about this, so I headed to the Australian War Memorial’s website, and looked up their Battalion War Diaries which you can find online now. Found the one for the 2/48th Battalion, scrolled through to find the page relating to 1 June 1945 … and bingo!

The entry for 1 June 1945, says the following …Date: 1 Jun to 30 Jun 45

Place: Tarakan

Date: 1 Jun 45

Hour:

Summary of Events and Information:

Following a successful air strike by 18 Liberators each carrying 9 x 500 lb bombs and 24 Lightnings with Napalm and staffing, B Coy attacked the 102 feature. 12 Pl moved forward and killed 6 enemy in their positions. Moving back to their positions. These were quickly engaged by the flame throwers and the enemy party destroyed. 12 Pl now over-ran the 102 feature. 10 Pl passed through and exploited for approx 200 yards West of 102 without making contact.On other coy fronts, patrols were active throughout day. 16 Pl engaged an enemy standing patrol of 6 astride creek jun at 436683 but results could not be observed. The Pnr Offr (Lt SIMPER), 4 Pnrs and 9 ORs from A Coy engaged a patrol of 12 Jays at 444684 killing two and wounding one.

Changed to Bn’s dispositions: B Coy on 102 Feature.

Enemy cas for 24 hrs: 12 killed, 1 probably killed.

Own cas for 24 hrs: KIA -, WIA 1 offr 1 ORpage 1, from the Unit 2/48 AIB,War Diary, 1-30 June 1945 [AWM, ref: RCDIG1023631]

[click for a larger image]

Roy was there. He saw this happen. He saw the action, and he drew it. And this precious WW2 momento is still in the family.

After five years of travelling to various parts of the world fighting as a proud Australian, and surviving several gunshot wounds and other illnesses, Roy returned home to his wife, Vera in South Australia and settled into life after war. No doubt his injuries took their toll, as he died relatively young, at age 58, and is buried at Cheltenham Cemetery in South Australia.

Vera and Roy never had any children, so they don’t have any direct relatives, and Roy died before I was born so I never knew my great uncle, but despite that I wanted pay tribute to him.

Lest We Forget

“Dead” Soldier Returns

Anzac Day. The day to remember those who fought for our country. Some survived. Many didn’t. And in reality those that returned were changed forever.

It was while I was going through the military records of Arthur Vincent Elphick (Mr Lonetester’s great grandpa), that I kept seeing the name of Donovan Russell Elphick written in his records. Arthur was one of twelve children in the family, and Donovan was his youngest brother.

On checking Donovan’s military records on the National Archives of Australia website, and reading through the dossier, one page in the record jumped out at me. But firstly, some background information …

Born in Prospect, South Australia, but living in Western Australia, 24 year old Donovan signed up to serve his country in January 1915. After training in Western Australia, he was assigned to the 5th Reinforcements 11th AIF, and sailed to Egypt in June 1915, and was obviously in the thick of it from arrival, as within a week of arriving he was in hospital suffering from “deafness”.

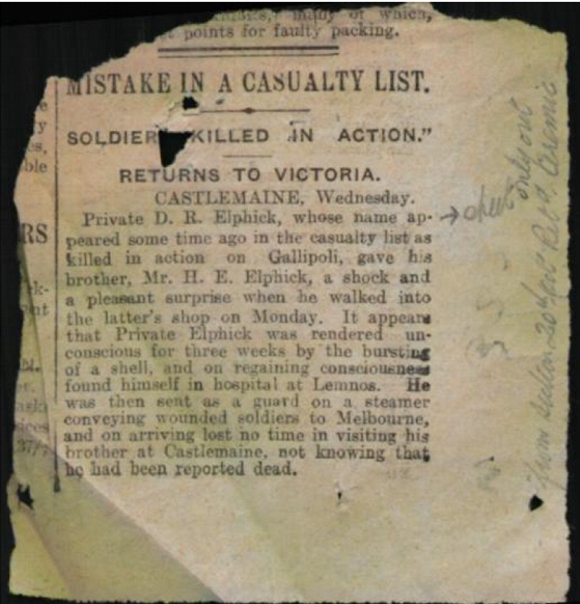

From here, I’ll let you read the article as that explains it all …

The above article came from a Victorian newspaper, and is dated 20 October 1915. This story was repeated in numerous Victorian, South Australian and Western Australian newspapers over the weeks following. As you can imagine it was quite a story. And to say that it shocked his brother (Harold), when he walked in would be an understatement.

Donovan was one of six boys in the family, with three going off to war. Sadly only two returned.

And while Donovan Elphick did survive World War 1, he died in Perth on 25 December 1936, aged just 45.

Reminiscences of WW2 from My Grandparents – Part 2

ANZAC Day. A day that Australians and New Zealanders remember of those who went to war. A day to remember those who never made it home. And it is also a day to remember those who were left at home during the war and afterwards.

Last week I wrote “Reminiscences of WW2 from My Grandparents – Part 1” which is primarily an interview with my grandparents Evelyn and Cecil Hannaford about their experiences during World War 2.

This interview, which was done as a high school project a number of years ago by a friend who interviewed them, is written as a transcript. So this is my grandparents talking about their own experiences during the war, In. THEIR. OWN. WORDS! Not as history books records it, but as they experienced it.

As it was a long interview I decided to split it into two, and this is the continuation.

Continuation of the interview …

What type of weather was it?

Mr H. It was winter time. Then when we got up to Trincomalee [Sri Lanka] it was summer time, in the tropics. We were out in the bay and the sister ship, Mary, went out into the harbour and they had all the port holes open, light shining everywhere. We had to have ours shut and it was hot.

Did you have enough food?

Mrs H. Well, everyone was rationed.

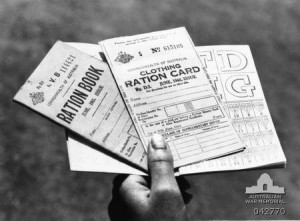

What were the ration books like?

Mrs H. We were given ration books and you had to have so many coupons for tea and sugar and butter. We weren’t troubled about the butter because we made our own.

Mrs H. We had to go to the shop or on the other hand thee was one of the grocers that used to come around and take the order and then deliver it the next week. You always had to have your order for the next week ready. Another thing that was scarce was steel. When that went out we had no steel wool for the pots and pans. That all had to go into the bullets and so forth. There were quite a few things like that … silvo, brasso.

Mr H. Because the troops had to polish their buttons. No. They did it in the early days, but during the war they didn’t. Couldn’t have anything shiny.

Mrs H. Anyway, the ration books were a pesky nuisance. I think we had to have them for clothing eventually. It started off just with the eats and then it got down to the clothings, sheets, things like that.

Mr H. Petrol. You were only allowed a certain number of gallons. About so much a week or a month.

Mrs H. Your coupons would accumulate with petrol. Because if you didn’t use it one week you could get the two lots the next. But it was always safer to get it each week, otherwise somebody else might have got in before you and got the extra.

Who told you where you had to work?

Mr H. There was a man power committee or something, under the government.

Mr H. You had to register.

Mr H. They directed labour to certain industries.

Mrs H. You put down what you wanted to do or where you prefer to go, and what your present occupation was, whether you were on a farm, or what you were doing. Anyhow, they said I couldn’t go to the engineering department and so I had to stay on the farm and help with the vegetables. Because all the men were taken.

Mrs H. When one brother went into the army, it just left the other brother at home. So when it was to feeding cows and that sort of thing, that was how I learnt to drive the car. But it was the tractor I learnt on and then I rose to the car!

So you really learnt independence then?

Mrs H. Yes.

What was it like just having one man around?

Mrs H. It was pretty awful at times. It anything happened to him, I would have to the do the milk round, like if he got sick or anything, because had a milk round as well.

Did you have to take and precautions in case of an attack?

Mrs H. Yes. We had to black out every night. That was putting black coverings over your windows, so you couldn’t see any lights. We had to black out anywhere where there was a likelihood of light getting through. Churches had to have the same thing. Well, all public places had to do it as well as the homes.

Mr H. All the cars had to have the top half of their lights painted black, dimmed. So it only showed a little bit of light down on the road. Pretty hectic driving in those days.

Mrs H. I don’t think your car was used much through the war years. I think we walked everywhere.

Mr H. We had to save petrol, didn’t we.

Mrs H. Yes. But it was illegal to have any lights shining.

What would they do it they saw them?

Mr H. Probably be fired.

Mrs H. Be told off or whatever.

Did you ever feel that Australia would be invaded?

Mrs H. When it got to Darwin we certainly did. It got a bit close to home.

How did you feel when you heard about the bombing of Darwin?

Mrs H. It made your heart sink a bit. It was Australia. Your country.

Were you married before you (Mr H.) went?

Mrs H. Yes. It was two or three months after we married that you (Mr H.) went.

Was that hard, him going?

Mrs H. It made you wonder what had happened.

How did you feel when you heard about the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and then on Nagasaki in 1945?

Mrs H. Oh! Terrific. I threw my hands and through “that will be the end of it”.

How did you feel when the war ended?

Mrs H. V for Victory. We had to put up two fingers, V. V for Victory!

Did you celebrate in any way?

Mr H. We were together at the Park when peace was declared.

So you (Mr H.) were back in Australia?

Mr H. Yes. Actually I was released before the end of the war. Because it must have been when the bomb hit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they could see the end in sight and so quite a few of us were released. I didn’t go to the islands at all. As far as I got was Queensland, after I came back from the Middle East. Then stayed at Cairns, Atherton for quite a while.

Mrs H. He had a brother, younger that was in the gunners (artillery) and they were bringing him back to the Islands.

Mr H. He was at Rabaul, New Britain. He was there all the time. The Japs got him there.

Mrs H. They’ve never heard of him since.

What was it like coming home from the war?

Mr H. Quite a thrill. Glad to be back and forget all about it.

Mrs H. We met in Rundle Street. It was by accident.

Mr H. That was when we came back from the Middle East. I got out on leave and was going to go home with a carrier who used to come up to Cudlee Creek, used to run through Lobethal. Anyway, I didn’t have any pyjamas and I had to go and get a pair. So I went up to Gibsons and bought a pair of PJs. Mum (Mrs H.) was in a little restaurant just below Gibsons and as I walked past she must have spotted me.

So what did you do?

Mr H. She came home with me then!

So it was quite a shock. Were you going to surprise her?

Mrs H. They never let you know their movements.

Mr H. I never expected to see anyone in town. I intended to get home anyway.

What did you do after the war?

Mr H. Lived at Cudlee Creek, where we live now.

Mrs H. When Hiroshima was bombed, these guys didn’t have to go back in to the army and so that was the end of it. So then you (Mr H.) applied to get out and he was given it.

Do you have any other experiences?

Mr H. I remember one night we were camped along the beach at El Alamein. During the day we used to go up onto a hill and overlook the enemy. I used to drive this armoured car up and park it in a little dugout and then they would go up in this little cave and watch. All I had to do was wait at the car. Anyhow, at night, we used to go down to the beach and camp on the sandhills. We would make our bed alongside a “slit trench’. Which was a narrow trench, just big enough to slide into. We would make our bed by there in case of any enemy attack. This particular night there was an attack and what we did was we just rolled into the trenches.

Mr H. There were a few shots fired. Another chap had his tyre punctured up on his car, but the armoured car I had didn’t have any damage done to it. None of us were injured at all, so that was alright.

Mr H. One thing about being in the artillery was that we were quite a long way back from the fighting.

Did you hear the guns?

Mr H. Oh yes, you could hear them.

How did you feel?

Mr H. It was a thrill on the opening night at El Alamein, because there were big guns behind us and then our lot and then the smaller guns further on. The noise was terrific. you got used to it after a while.

Mrs H. One of the lads that came home said that he was in the aircraft, anyway he reckoned that whenever the guns were firing you felt as big as a house because bullets were falling all around you and you thought “it will be me next”.

Were you glad that you weren’t fighting?

Mr H. Yes. Yes. I never intended to take on the infantry, because that was just not my piece of cake. Some of the chaps they seem to like it.

Mrs H. Some were more daring that others.

What did you think of Hitler?

Mr H. He was a nasty man. Mussolini wasn’t much better.

Mrs H. They were two of a kind.

Mr H. Much alike.

After Dunkirk, when Churchill was saying “Don’t give up, keep on going”.

Mrs H. He was the one that kept the army together.

Mr H. Churchill had such a wonderful personality. A good leader.

Mrs H. He was a good soldier himself. He knew how to get the best out of people.

Mr H. If he wasn’t there it might have been quite a different story.

——————

Between my earlier post and this one they cover the greater portion of the interview, but not the entire thing.

Before finishing I really must thank Cathryn Trollope, again for not only allowing me to use her interview in my blog, but also for asking if my grandparents would be interested in doing the interview in the first place. Myself, together with other family members wholeheartedly THANKYOU!!