The Train, the Explosion, and the Parliamentarian

The year was 1890, and …

“a most painful accident, of a character unparalleled in the annals of railway accidents in this colony, if not in Australasia, occurred on the Northern line on Friday evening, Jan. 17. The terrible calamity which befel … was so sudden, and its effects so appalling, that the harrowing details were listened to with bated breath and unconcealed sorrow.”

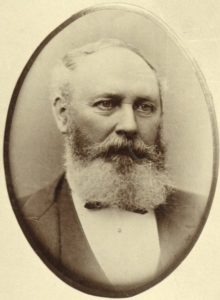

That’s how the long article about the tragic death of well-known South Australian businessman and parliamentarian, Honorable James Garden Ramsay, M.L.C. begins.

James Ramsay was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1827, did an apprenticeship as an engineer at the St Rollox Ironworks in Glasgow, and then emigrated to South Australia in 1852. He established an agricultural implement and machine manufacturing plant at Mount Barker, which represented the starting point of what later grew into the largest business of its kind in the colony. Apart from his Mount Barker business, he opened up agricultural implement manufacturing businesses in Adelaide, Clare and Laura as there was a huge demand.

Anyway J.G. Ramsay’s interest in politics began in the 1860s, and in 1870 he entered Parliament for Mount Barker, and from then until his death he held various parliamentary positions. The article says …“Altogether he served over five years as a Minister of the Crown. As leader of the Legislative Council he exhibited considerable tact and ability, and possessing the confidence of his fellow members, he was eminently successful in conducting the business”.

Which then brings us back to Friday evening, 17 January 1890 when James Ramsay is travelling back to Adelaide, from Saddleworth, South Australia by train. Travelling with Mr Rounsvell (a fellow M.P.), who by the time the train reached Riverton left to go to the smoking carriage, after which Mr Ramsay fell asleep while reading the newspaper. The following is the report of what happened …

“The Hon. gentleman was left by himself, and he laid down on the seat, and after reading a newspaper fell asleep. Just before the train reached Stockport he was awakened by a loud report, which proved to be the bursting of the lamp, and in an instant he was all ablaze, the burning oil falling all over him. He tried to open the door of the carriage, but was unsuccessful, and it was not until the train arrived at Stockport that he was enabled to roll on to the ground in a terrible condition. Assistance was at once procured, and he was wrapped in a rug and some bags, the flames in this way being extinguished. It was then seen that Mr. Ramsay was in a very serious condition, and that he was suffering the most acute pain. Telegrams were dispatched to Gawler and Adelaide, and at the former place the sufferer was met by Dr. Popham, who advised his being conveyed on to Adelaide.”

Badly burnt, Mr Ramsay was met at the Adelaide train station by Dr Marten, his brother John Ramsay and a waiting ambulance.

“Dr Marten found him very much collapsed, suffering greatly from the shock. He was lying on the floor of the carriage, partially covered with rags, most of his clothes being burnt off. He was at once removed int he ambulance van the Patients’ Home on South-terrace, where his wounds were dressed by Dr. Marten. He still retained consciousness, notwithstanding the effects of the shock. The extent of the injuries were then ascertained, and the sufferings of the unfortunate gentleman must have been intense. He was burnt from head to foot, the skin being taken off from all parts with the exception of the head. His beard was completely destroyed, and his eyebrows and eyelashes singed. Te skin came off the left hand like a glove, the left having suffered more than the right, the burns extending up to the armpit. The injuries were greatest about the abdomen and the arms, though the whole body was badly burnt.”

His wife who was at Mount Barker at the time, was advised of the accident on Friday evening, and made her way to the city, reaching Adelaide by 5am on Saturday morning. However, sadly due to the severity of the burns, James Garden Ramsay passed away on Saturday 18 January 1890, at about 10.30am.

He was a migrant who certainly left his mark in South Australia in business, politics and the local community where he lived. This shows simply by the number of articles written in newspapers all around Australia about his death (over 8500. Yes, seriously!!).

Thanks to Trove, you can read the FULL article about the accident from the report in the Adelaide Observer, Saturday 25 January 1890, click here, and for further information, click on the links below.

More information:

James Garden Ramsay on Wikipedia

Read the Adelaide Observer article in full here

You can find details of the inquest here

His obituary is printed in the South Australian Register here

And for odles more articles on his death click here

The Duel in the City of Adelaide

A duel is something you associate with westerns. Two cowboys pacing it out on a dusty street before turning around, and drawing their guns as quick as possible. And usually the fastest one wins.

So when I found out that there was a duel in my hometown city of Adelaide, South Australia naturally I was intrigued, and had to check it out further.

There was no cowboys, or dusty streets, or tumbleweeds in this duel … (actually the streets may well have been dusty still at this stage), but certainly no cowboys or tumbleweeds. Instead we had politicians!

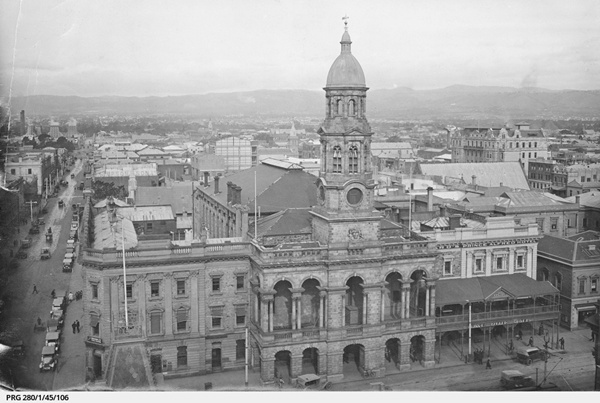

The two players in this duel are Charles Cameron Kingston, Q.C. & M.P., (1850-1908) and Richard Chaffey Baker, M.L.A. (1841-1911). The scene was the Adelaide Town Hall, on King William Street, Adelaide, and the time was 1.30pm, on Friday, 23 December 1892 … and it all started over name calling!

The Australian Dictionary of Biography sums up the who episode quite succinctly in the following paragraph …

“The most dramatic and colorful episode in Kingston’s political career occurred in 1892. After a prominent conservative member of the Legislative Council, (Sir) Richard Baker, denounced him as a coward, a bully and a disgrace to the legal profession, Kingston responded by describing Baker as ‘false as a friend, treacherous as a colleague, mendacious as a man, and utterly untrustworthy in every relationship of public life’. Kingston did not stop there. He procured a pair of matched pistols, one of which he sent to Baker accompanied by a letter appointing the time for a duel in Victoria Square, Adelaide, on 23 December. Baker wisely informed the police who arrested Kingston shortly after he arrived, holding a loaded revolver. Amidst widespread publicity he was tried and bound over to keep the peace for twelve months. The sentence was still in force when he became premier in June 1893.”

But the best description I’ve found of the whole saga (and there’s literally hundreds on Trove), is one from a Sydney newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, dated Saturday 24 December 1892 …

“Considerable excitement was caused in the city to-day when a rumor gained currency that Mr. C. C. Kingston, Q.C., M.P., had challenged Mr. R. L. Baker, M.L.C., to a duel over a feud which lately has been brought prominently before the public in Parliament and elsewhere. Many rumors are in currency with reference to the affair. As far as can be ascertained the facts are these.”

It goes on …

“A messenger called at Mr. Baker’s office in the city with a package and a letter from Mr. Kingston, which was stated to be “important” by the messenger. Mr. Baker was attending a meeting of the Queensland Mortgage Company, of which he is chairman of directors, and did not receive the communication till 1 o’clock. The letter asked Mr. Baker to meet Mr. Kingston in front of the Town-hall at 1.30 that day. The package accompanying the letter contained a revolver and cartridges. The police were communicated with on the matter; and Detective Kitson and Constable Rea awaited near the square at the time appointed. It is understood that Mr. Baker sent word to Mr. Kingston that he would attend as requested. At the hour named Mr. Kingston, with a six-chambered revolver, fully loaded, went to the square, where he was taken charge of by the officers of the law. It is stated that Mr. Kingston resisted the efforts of the police to secure possession of his revolver, and that Mr. Baker also kept his appointment. Mr. Kingston was detained at the police station for some time, and then released.”

The article goes into what provoked the reaction:

“The trouble arose as follows: Mr. Baker, in a letter to Sir Edwin Smith, which was read in tho Assembly, attacked Mr. M’Pherson and the Trades and Labor Council, whereupon Mr. Kingston severely criticised Mr. Baker’s conduct. Tho latter replied in the Council in a speech in which he stigmatised Mr. Kingston as a “bully and a coward,” and said that the Wheat Rates Committee had found him “guilty of untruth.”

Questions were later asked of Mr Baker as to why he declined taking part in the duel, the following article from the Wagga Wagga Advertiser, on 31 December 1892 explains his reasons

“I had two reasons,” continued Mr. Baker, ” for declining a meeting with Mr. Kingston. One was that, though I was not afraid of him, or of being shot by him, I was afraid of breaking the law and of either being hung for murder or sent to gaol for the rest of my life. Under these circumstances I left the matter entirely in the hands of the Government, in the full belief that the Government would vindicate the law. “

So, yes a duel was scheduled … but no, it never actually happened, thanks to the authorities being notified. But even so, what a sensation it caused. And if you want to read more about it, here’s a link to over 200 articles on Trove about it.

They Died in the Asylum

Parkside Lunatic Asylum is the original name for the building that was subsequently renamed to Parkside Mental Hospital, then Glenside Hospital and more recently Glenside Health Services.

Situated on Fullarton Road at Glenside, it is in one of Adelaide’s leafy eastern suburbs and is by outwards appearance, a magnificent place. But the asylum was far from that for the inmates at the asylum, and sadly for so many it was their last home.

The Parkside Lunatic Asylum was opened in 1870 initially housing men, but by the 1880s men, women and children were being housed there. It housed not only those suffering from mental illness, but also people with intellectual disabilities and medical conditions like epilepsy.

While browsing around on Trove, I found this article in the Adelaide Advertiser, 14 January 1910, and was saddened by the fact that there was so many who even in a six month period, died without family nearby.

– Wilhelm Heinrich Dittich (71), July 5, pulmonary disease and cardiac failure

– Judy (aboriginal female), (60), July 10, gastritis and cardiac failure

– Guiseppe Castagneth (58), August 8, apoplexy and cerebral disease

– Rosalie Russell (63), August 20, hepatic disease and ascites

– Theodosia Byrne (78), August 20, apoplexy and senile decay

– Sarah Jane Hayes (35), August 29, phthisis and exhaustion

– Bridget (alias Annie) Evans, (42), August 29, suicide by hanging

– William Conway (36) September 1, general paralysis and apoplexy

– Dora Knout (80), September 2 cardiac disease and senile decay

– William Carruthers (75), September 5, diarrhoea and senile decay

– Thomas Paddock (70) September 17, cardiac disease and senile decay

– Alfred Perfect (48) September 18, apoplexy and paralysis

– George Henry Holmes (52), September 26, pulmonary tuberculosis and exhaustion

– Isaac Mowatt (69), November 2, empyæmia

– Mary McNulty (60), November 13, Pulmonary tuberculosis and exhaustion

– Oscar Genske (55), December 6, cardiac disease and paralysis

– John Kew Dawson (69), December 10, senile decay and exhaustion.

Glenside Hospital, formerly the Parkside Lunatic Asylum, taken 2015

Source: denisbin Flickr

– Parkside Lunatic Asylum on Find & Connect

– Untold Stories of the Parkside Lunatic Asylum on Weekend Notes

Emigration from England to South Australia in the 1800s

The “Mayflower” is ‘the ship’ in US history. The first ship to transport passengers from England to the United States in 1620. 102 people, all hoping to start a new life on the other side of the Atlantic.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

From then on, there was a big push to get skilled labourers from England to emigrate to the new colony, and as an enticement they were offered free passage (assisted passage). Of course there was still the option for anyone who wished to emigrate to pay their own way (known as unassisted passage), but many took up the offer of the emigration scheme, and as a result these pioneers helped make South Australia what it is today.

But as with anything that’s free, there were some rules and regulations.

I came across this list of rules for those wanting assisted passage in the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, dated 27 February 1839, and it’s truly fascinating.

RULES FOR EMIGRATION

- The Act of Parliament declares that the whole of the funds arising from the sale of lands, and the rent of pasture, shall form an Emigration Fund, to be employed in affording a free passage to the Colony from Great Britain and Ireland for poorer persons; “provided that they shall, as far as possible, be adult persons of both sexes in equal proportions, and not exceeding the age of 30 years.”

- With a view to carrying this provision into effect, the Commissioners offer a free passage to the Colony (including provisions and medical attendance during the voyage) to persons of the following description.

- Agricultural laborers, Shepherds, Bakers, Blacksmiths, Braziers, and Tinmen, Smiths, Shipwrights, Boat-builders, Butchers, Wheelwrights, Sawyers, Cabinetmakers, Coopers, Curriers, Farriers, Millwrights, Harness-makers, Lime-burners, and all persons engaged in the erection of buildings.

- Persons engaged in the above occupations, who may apply for a free passage to South Australia, must be able to give satisfactory references to show that they are honest, sober, industrious, and of general good character.

- They must be real laborers, going out to work for wages in the colony, of sound mind and body, not less than 15, nor more than 30 years of age, and married. The Marriage Certificate must be produced. The rule as to age is occasionally departed from in favour of the parents of large families.

- To the wives of such laborers as are then sent out, the Commissioners offer a free passage with their husbands.

- To single women a free passage will be granted, provided they go out under the protection of their parents, or near relatives, or under actual engagement as servants to ladies going as cabin passengers on board the same vessel. The preference will be give to those accustomed to farm and dairy work, to seamstresses, strawplatters, and domestic servants.

- The children of parents sent out by the Commissioners will receive a free passage, if they are under one, or fall 15 years of age at the time of embarkation. For all other children £5 each must be paid before embarkation by their parents or friends, or by the Parish. It will be useless to apply for a relaxation of this rule.

- Persons who are ineligible to be conveyed out by the Emigration Fund, if not disqualified on account of character, will be allowed to accompany the free Emigrants on paying to the commissioners the bare contract price of passage, which is usually between £15 and £17 for each adult person. The charges for children are as follows: under one year of age, no charge; one year of age but under seven, one-third of the charge for adults; seven years of age and under fourteen, one-half the charge for adults. A passage intermediate between a cabin and steerage passage may also be obtained of the Commissioners at a cost exceeding that of the steerage passage by one-half. Each intermediate passenger is entitled to half a cabin with some slight comforts in addition to those enjoyed by the steerage passengers.

- All Emigrants, adults as well as children, must have been vaccinated.

- Emigrants will, for the most part, embark at the Port of London, but if any considerable number should offer themselves in the neighbourhood of any port of Great Britain or Ireland, arrangement will, if possible, be made for their embarkation at such port.

- The expense of reaching the port of embarkation must be borne by the emigrants, but on the day appointed for their embarkation, they will be received, even though the departure of the ship should be delayed, and will be put to no further expense.

- Every adult Emigrant is allowed to take half-a-ton weight or twenty measured cubic feet of baggage. Extra baggage is liable to charge at the rate of £2.10s the ton.

- The Emigrants must provide the bedding for themselves and children, and the necessary tools of their own trades; the other articles most useful for emigrants to take with them, are strong plain clothing, or the materials for making clothes upon the passage. In providing clothing, it should be remembered that the usual length of the voyage is about four months.

- On the arrival of the Emigrants in the colony, they will be received by an Officer, who will supply their immediate wants, assist them in reaching the place of their destination, be ready to advise with them in case of difficulty, and at all times give them employment at reduced wages on the Government works, if from any cause they should be unable to obtain it elsewhere. The Emigrants will, however, be at perfect liberty to engage themselves to any one willing to employ them, and will make their own bargain for wages. This arrangement, while it leaves the Emigrant free to act as he may think right, manifestly renders it impossible for the Commissioners to give any exact information as to the amount of wages to be obtained; they can merely state that hitherto wages have been very much higher than in England.

So a free passage together with the social and economic conditions in England at the time, enticed our ancestors to pack up their whole life, spend four months on board a ship, travelling to an unknown country on the other side of the world, to start start again. We can’t imagine it can we.

The pioneers. They were brave beyond our understanding.