Britain’s Playing Card Tax

Anyone who is vaguely familiar with British social history will be aware that they have had some “different” (by that, yes I mean rather odd) taxes over the years.

Take for instance the Hearth Tax in which you paid based on the number of fireplaces in your house, the Window Tax was the same but was based on the number of windows you had. The Clock Tax, the Candle Tax, the Soap Tax, even a Beard Tax are others just to mention a few – and all were used as a means to raise funds for the government of the day.

But here we’re talking about a tax on Playing Cards.

Yes, truly. The humble deck of cards was taxed (not forgetting dice as well).

In reality they had been taxed since the late 1500s, but in 1710 the English Government dramatically raised the taxes on them, which the manufacturer was then liable for. As the rate of tax was equivalent to 12 times the price of a cheap pack of cards, you can imagine that there were forgeries.

But in a bid to prevent this, each manufacturer had their own ‘mark’, and would hand stamp their mark on the Ace of Spades to show that it was a legit version.

Still, as the taxes were excessive, forgeries happened.

And while creating forgeries of playing cards doesn’t sound too drastic, if you were caught making them the result was hanging.

While the tax itself is surprising enough, what’s even more surprising is that tax continued through until 1960. That’s 250 years! Incredible.

So if you are lucky enough to have an old deck of cards, take a closer look at it. Check out the maker, and in particular have a close look at the Ace of Spades and see if it has the hand stamp on it.

15 April 1912 – The Day the “Titanic” Sank

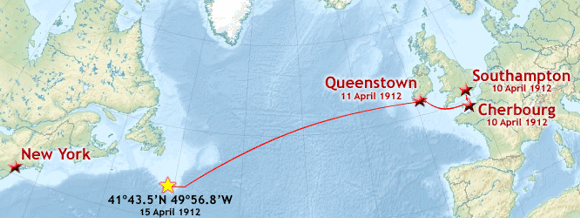

It was a disaster like no other at that time. The world’s biggest (and self-proclaimed ‘unsinkable’) ship set off from Southampton on 10 April 1912, bound for New York. It was her maiden voyage, and the crowd seeing it off was huge. Little did they know that just 5 days later all onboard would be fighting for their life, with the vast majority not making it.

2.20am, 15 April 1912, just a mere 2 hours and 40 minutes after hitting an iceberg in the Atlantic Ocean, the unthinkable happened to the unsinkable. The Titanic sank.

Route of Titanic’s first/last maiden voyage, 10-15 April 1912

(Creative Commons licence, Prioryman)

total capacity: 3547 passengers and crew

total onboard: 2206 passengers and crew

total survived: 703 passengers and crew

That was 105 years ago, and it still has an impact.

The movie below is from British Pathè’s collection, and is just one of the 85,000 old movies they have made freely available. Showing actual footage of the ship, the rescue ships, together with interviews of some survivors, it is chilling.

There’s no doubt that the Titanic has become the stuff of legend.

I remember asking my grandma about it though she wasn’t born at the time, but her older sisters were, and they remembered it, being aged 11 and 12.

So I decided to see what the local South Australian newspapers wrote about it.

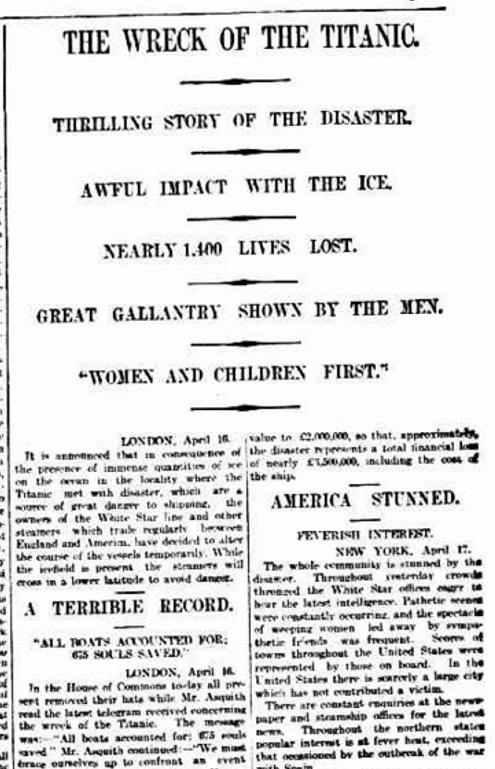

The following was the first report of it in South Australia’s “The Advertiser”, was was dated 18 April 1912. Not too bad considering that communication back then wasn’t as instant as we have today. It didn’t make front page like it did in the US or England, but it did make a big article on page 9. The article blow is just a small portion of it.

The Wreck of the Titanic, (18 April 1912, The Advertiser , p. 9.) http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5336985

And as you would expect, every Australian newspaper ran the story, together with all the reports afterwards. For newspapers just in South Australia, and just in April 1912, Trove has 1000 articles. I’ll admit it, I didn’t read them all.

There’s no doubt this tragedy rocked the world, but something that I was reminded of reading a current news article relating to the 105th Anniversary of this event, was of those who had to go out afterwards and “collect the dead”. We tend to think of the rescuers, but forget about those who went in afterwards.

“As rescue ships approached the ghostly sea where the Titanic plunged into the ocean in the dead of the cold night on April 15, 1912, white specks began to appear in the distance. To onlookers aboard, they looked like “clustering and moving along the waves like a flock of seagulls”. Hundreds of them. All grouped together. The white specks were frozen bodies of the dead, wrapped in the ill-fated steamer’s life belts. For days, great quantities of these bodies, along with doors, pillows, chairs, tables, and scattered remains, floated along the North Atlantic.”

You can read the “Rescue Crews Reveal the Grisly Aftermath of the Titanic Tragedy” here.

So on this day, 105 years on, we remember not only those who lost their life and their families, as well as who were fortunate enough to survive this tragedy, but also those who had the horrific task of “cleaning up” afterwards. Every one of them would have had their life changed from the events that took place on 12 April 1912.

More info on the Titanic:

For more Titanic related old movies from British Pathè click here

100 Facts about the Titanic

Timeline of the Titanic

Wikipedia’s entry for RMS Titanic

Please Note: there are slight discrepancies in the number who died, and the number who survived. One articles says 703 survived, another says 706, another says 705. Another article says 1503 died, another 1517. I’m no professional historian, so I can’t say for sure which is the real figure, but it would be a matter of looking further at how each have calculated their numbers.

Emigration from England to South Australia in the 1800s

The “Mayflower” is ‘the ship’ in US history. The first ship to transport passengers from England to the United States in 1620. 102 people, all hoping to start a new life on the other side of the Atlantic.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

Well, in South Australian history the “Buffalo” is the equivalent. It was one of a fleet of ships to arrive in the colony at the end of 1836. Once it arrived at Glenelg, Governor John Hindmarsh who was on board, proclaimed the establishment of government in South Australia as a British province.

From then on, there was a big push to get skilled labourers from England to emigrate to the new colony, and as an enticement they were offered free passage (assisted passage). Of course there was still the option for anyone who wished to emigrate to pay their own way (known as unassisted passage), but many took up the offer of the emigration scheme, and as a result these pioneers helped make South Australia what it is today.

But as with anything that’s free, there were some rules and regulations.

I came across this list of rules for those wanting assisted passage in the West Briton and Cornwall Advertiser, dated 27 February 1839, and it’s truly fascinating.

RULES FOR EMIGRATION

- The Act of Parliament declares that the whole of the funds arising from the sale of lands, and the rent of pasture, shall form an Emigration Fund, to be employed in affording a free passage to the Colony from Great Britain and Ireland for poorer persons; “provided that they shall, as far as possible, be adult persons of both sexes in equal proportions, and not exceeding the age of 30 years.”

- With a view to carrying this provision into effect, the Commissioners offer a free passage to the Colony (including provisions and medical attendance during the voyage) to persons of the following description.

- Agricultural laborers, Shepherds, Bakers, Blacksmiths, Braziers, and Tinmen, Smiths, Shipwrights, Boat-builders, Butchers, Wheelwrights, Sawyers, Cabinetmakers, Coopers, Curriers, Farriers, Millwrights, Harness-makers, Lime-burners, and all persons engaged in the erection of buildings.

- Persons engaged in the above occupations, who may apply for a free passage to South Australia, must be able to give satisfactory references to show that they are honest, sober, industrious, and of general good character.

- They must be real laborers, going out to work for wages in the colony, of sound mind and body, not less than 15, nor more than 30 years of age, and married. The Marriage Certificate must be produced. The rule as to age is occasionally departed from in favour of the parents of large families.

- To the wives of such laborers as are then sent out, the Commissioners offer a free passage with their husbands.

- To single women a free passage will be granted, provided they go out under the protection of their parents, or near relatives, or under actual engagement as servants to ladies going as cabin passengers on board the same vessel. The preference will be give to those accustomed to farm and dairy work, to seamstresses, strawplatters, and domestic servants.

- The children of parents sent out by the Commissioners will receive a free passage, if they are under one, or fall 15 years of age at the time of embarkation. For all other children £5 each must be paid before embarkation by their parents or friends, or by the Parish. It will be useless to apply for a relaxation of this rule.

- Persons who are ineligible to be conveyed out by the Emigration Fund, if not disqualified on account of character, will be allowed to accompany the free Emigrants on paying to the commissioners the bare contract price of passage, which is usually between £15 and £17 for each adult person. The charges for children are as follows: under one year of age, no charge; one year of age but under seven, one-third of the charge for adults; seven years of age and under fourteen, one-half the charge for adults. A passage intermediate between a cabin and steerage passage may also be obtained of the Commissioners at a cost exceeding that of the steerage passage by one-half. Each intermediate passenger is entitled to half a cabin with some slight comforts in addition to those enjoyed by the steerage passengers.

- All Emigrants, adults as well as children, must have been vaccinated.

- Emigrants will, for the most part, embark at the Port of London, but if any considerable number should offer themselves in the neighbourhood of any port of Great Britain or Ireland, arrangement will, if possible, be made for their embarkation at such port.

- The expense of reaching the port of embarkation must be borne by the emigrants, but on the day appointed for their embarkation, they will be received, even though the departure of the ship should be delayed, and will be put to no further expense.

- Every adult Emigrant is allowed to take half-a-ton weight or twenty measured cubic feet of baggage. Extra baggage is liable to charge at the rate of £2.10s the ton.

- The Emigrants must provide the bedding for themselves and children, and the necessary tools of their own trades; the other articles most useful for emigrants to take with them, are strong plain clothing, or the materials for making clothes upon the passage. In providing clothing, it should be remembered that the usual length of the voyage is about four months.

- On the arrival of the Emigrants in the colony, they will be received by an Officer, who will supply their immediate wants, assist them in reaching the place of their destination, be ready to advise with them in case of difficulty, and at all times give them employment at reduced wages on the Government works, if from any cause they should be unable to obtain it elsewhere. The Emigrants will, however, be at perfect liberty to engage themselves to any one willing to employ them, and will make their own bargain for wages. This arrangement, while it leaves the Emigrant free to act as he may think right, manifestly renders it impossible for the Commissioners to give any exact information as to the amount of wages to be obtained; they can merely state that hitherto wages have been very much higher than in England.

So a free passage together with the social and economic conditions in England at the time, enticed our ancestors to pack up their whole life, spend four months on board a ship, travelling to an unknown country on the other side of the world, to start start again. We can’t imagine it can we.

The pioneers. They were brave beyond our understanding.

The Top Hat, the Riot, and the £500 Fine

On this day 220 years ago, 15 January 1797, something lifechanging happened.

The world of fashion changed on that day. Top hats were created. Yes, that right.

The fashion icon of the upperclass and gentry in the Edwardian and Victorian eras, and a must have accessory for anyone who’s into Steampunk style, was created.

But not all went smoothly for the creator John Hetherington, as his newly designed head attire caused a riot. The condensed version of story is as follows …

The first Top Hat was worn by haberdasher John Hetherington on 15 January 1797, in London, England. When Heatherington stepped from his shop at 11am wearing his unusual headgear, a crowd quickly gathered to stare. The gathering soon turned into a crowd crush as people pushed and shoved against each other, resulting in a broken arm for one person there. As a result, Hetherington was summoned to appear in court before the Lord Mayor and fined £500 for breaching the peace. He was also charged with appearing “on the public highway wearing a tall structure of shining lustre and calculated to terrify people, frighten horses and disturb the balance of society”. However, within a month, he was overwhelmed with orders for the new headwear.

Trove has many articles detailing the “origin of the Top Hat”. Here’s a few of the longer versions of the story if you wish to check them out.

– How the First Silk Hat Startled London, Launceston Examiner, 17 February 1899

– The First Silk Hat, Evening News Sydney, 25 February 1899

– The First Top Hat, Canberra Times, 10 June 1927

Personally I’m totally thankful to John Hetherington, as I’m a lover of the Victorian era style, and really LOVE top hats, so much so that I wore one at my wedding!